The FogGuru Living Lab

Disclaimer: A previous version of this article has appeared in the IEEE IoT Newletter, March 2020.

Living labs are spaces for the coordination, research, design and validation of innovation projects. They are meant to seek for new technological innovations, methodologies or new combination of elements which could lead into an innovations adapted to people and society.

The FogGuru Living Lab aims to bring innovative Fog Computing technologies developed by the project’s early-stage researchers out of the lab and to apply them to a real use-case with technological as well as societal impact.

Potable water management issues

Potable water is a precious resource in many regions of the world, and particularly in semi-desertic areas such as the South of Spain [1]. Over the previous decade, the EMIVASA company, which is in charge of water management in the city of València, has been active at the forefront of IoT technologies [2]. EMIVASA deployed more than 420,000 smart water meters in every household which periodically report their readings through wireless networking technologies. The data are transferred in a data center and processed in various ways such as detecting water leaks or other incidents leading to abnormal water usage, which in turn brings considerable efficiency improvements to the management of precious water resources. However, this system relies on 15-years-old technologies. The wireless networking infrastructure carries only limited numbers of meter readings per day, which delays any incident detection. Different vendors impose the usage of different proprietary and mutually incompatible standards. Finally, deploying new functionality is not trivial. It is time to transition to more modern and open technologies.

The FogGuru European project aims to develop innovative Fog computing technologies and to train the next generation of European Fog computing experts. For us this constitutes an excellent opportunity to create a “Living Lab” with our partner Las Naves in València where we experiment Fog computing technologies in real settings, and demonstrate their usefulness to address real-world problems. Fog computing extends cloud computing deployments with additional compute, storage and networking resources located in the proximity of users and IoT devices [3]. Processing incoming data very close to their source allows one to reduce the pressure on the backhaul networking infrastructure, and may even allow disconnected operation in case of a failure of the device-to-cloud connection [4]. In the specific case of water management, we expect Fog computing technologies to bring faster detection of abnormal water consumption patterns, independence from the smart water meter manufacturers, and improved resilience and flexibility of the overall smart metering platform.

Integrating LoRaWAN with Fog computing technologies

We base our proposed solutions on the LoRa low-power wide-area network technology. LoRa supports wireless communications over very long distances (10km+), yet at the expense of an extremely limited available bandwidth per node. This fits the requirements of our use-case because each water meter reports only dozens of bytes of data at a modest frequency such as once every hour. On the other hand, the long range implies that we can cover an entire city with a small number of gateway nodes.

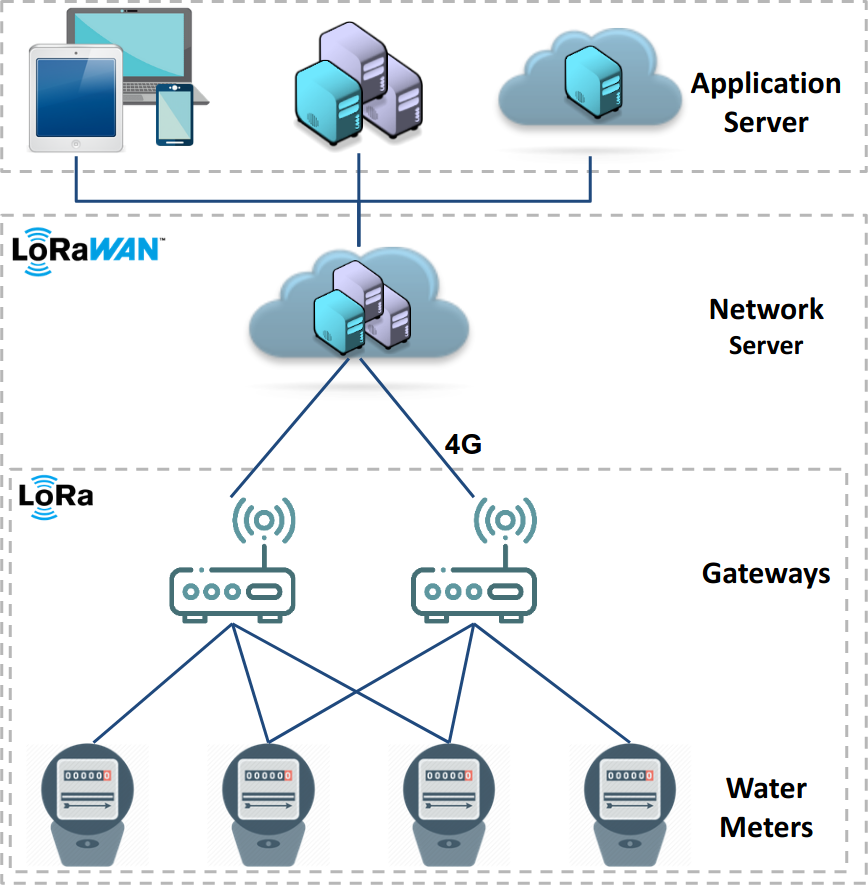

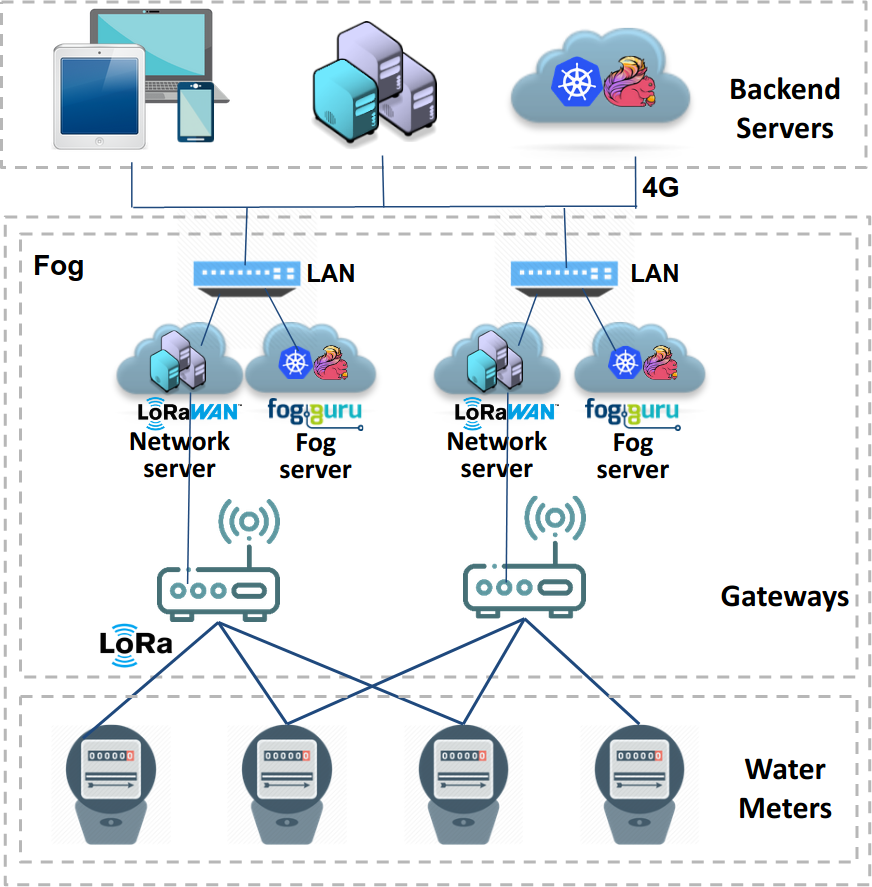

Fig. 1: Two potential system architectures.

The LoRa technology addresses only the low-level device-to-gateway communication. To design an entire infrastructure with multiple gateways, the LoRaWAN standard defines additional elements depicted in Figure 1a. The network server is in charge of detecting and removing duplicate messages received by multiple gateways from the same IoT device. The application server(s) are in charge of processing incoming data. The recent LoRaWAN v1.1 specification introduces additional components for device authentication and registration.

However, this architecture addresses the requirements only partially, as useful and sensible as it is. In particular, the reliance on a centralized network server implies that the messages originating from the water meters must traverse long network links before being processed in a single location. On the other hand, our goal is to process incoming messages as close as possible to the water meters, in the same location as the gateways that have received them.

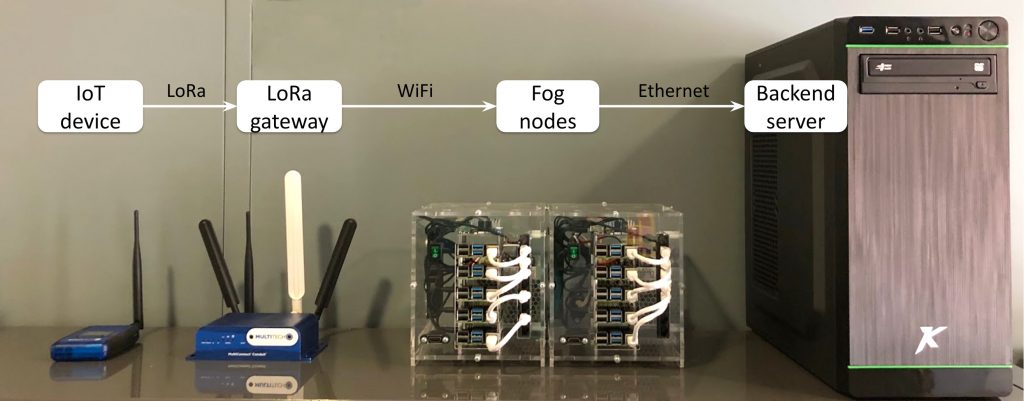

As shown in Figure 1b, we propose to equip each LoRa gateway node with its own dedicated network server. This allows the introduction of Fog computing servers in the same location, where incoming messages are processed immediately after having been received. The architecture still contains backend servers located in the cloud, where a final aggregation of pre-processed results by different Fog servers takes place, and where the operators control and visualize the status of the system. Figure 2 depicts parts of the experimental testbed.

Challenges

Building a prototype of an integrated Fog+LoRaWAN platform forces us to address a number of difficult research challenges.

- LoRa vendor independence: every LoRa gateway vendor integrates additional software such as a network server and an application server inside their gateways. However, these components often turn out to be proprietary and incompatible with one another. Since vendor independence is an important goal for this project, we prefer relying only on the simplest possible functionality of a LoRa gateway (namely packet forwarding between two networking technologies), and making use of open-source software such as the Chirpstack network server running in the Fog servers for all the other system components.

- Packet deduplication: one obvious drawback of a system architecture with multiple network servers is that we cannot rely any more on a single centralized network server to detect and filter duplicated messages received by multiple gateways. We are developing innovative techniques to allow multiple network servers to collaborate in order to realize the same function in a distributed way.

- System configuration: deploying multiple nodes in different locations immediately creates practical difficulties, even at a modest scale, for maintaining the correct software versions and configurations across the whole system. We are thus designing mechanisms to centralize these informations and distribute them on-demand to the respective nodes. Application development: data being produced by the smart water meters can be seen as a set of unbounded data streams. We expect that the same property will be true in numerous other IoT scenarios. We therefore plan to make use of data stream processing engines in the Fog nodes as the standard application development middleware in our system. We expect to use Node-RED for simple scenarios, and Apache Flink for more complex ones.

- Application deployment: we believe that a Fog computing platform should not be seen as a static environment dedicated to a single application. Instead, we envisage that many independent applications will be developed to process the incoming data in a variety of ways, and that such applications will be frequently deployed, re-deployed and eventually retracted from part or all of the Fog platform. To facilitate application deployment we rely on a modified version of Kubernetes designed for Fog computing scenarios [5].

Conclusion

The development of our experimental Fog+LoRaWAN platform is under way, and we expect to be able to start experimenting

it in real setting in the coming weeks. If everything goes according to plan, we will have demonstrated how Fog computing technologies may bring tangible benefits to the citizens of València thanks to improved management of their precious water

resources.

References

- UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage, “Irrigators’ tribunals of the Spanish Mediterranean coast: the Council of Wise Men of the plain of Murcia and the Water Tribunal of the plain of Valencia,” 2009.

- SmartH2O European Project, “Validation report,” Deliverable F7.2, Jul. 2016.

- IEEE Standards Association, “IEEE standard for adoption of OpenFog reference architecture for fog computing,” 2018.

- S. Noghabi, L. Cox, S. Agarwal, and G. Ananthanarayanan, “The emerging landscape of edge-computing,” ACM SIGMOBILE GetMobile, Mar. 2020,.

- A. Fahs and G. Pierre, “Proximity-aware traffic routing in distributed fog computing platforms,” in Proc. CCGrid, May 2019.